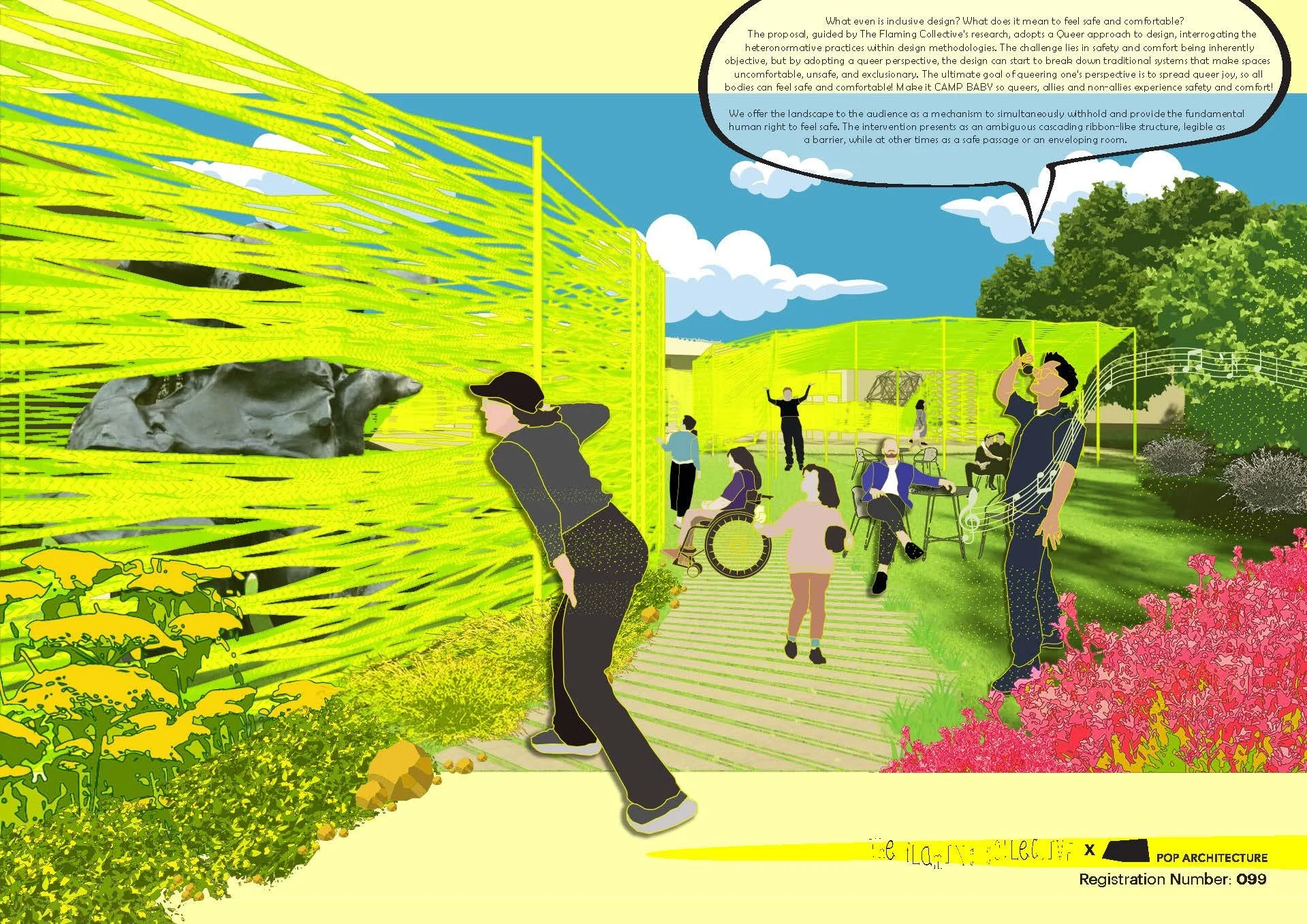

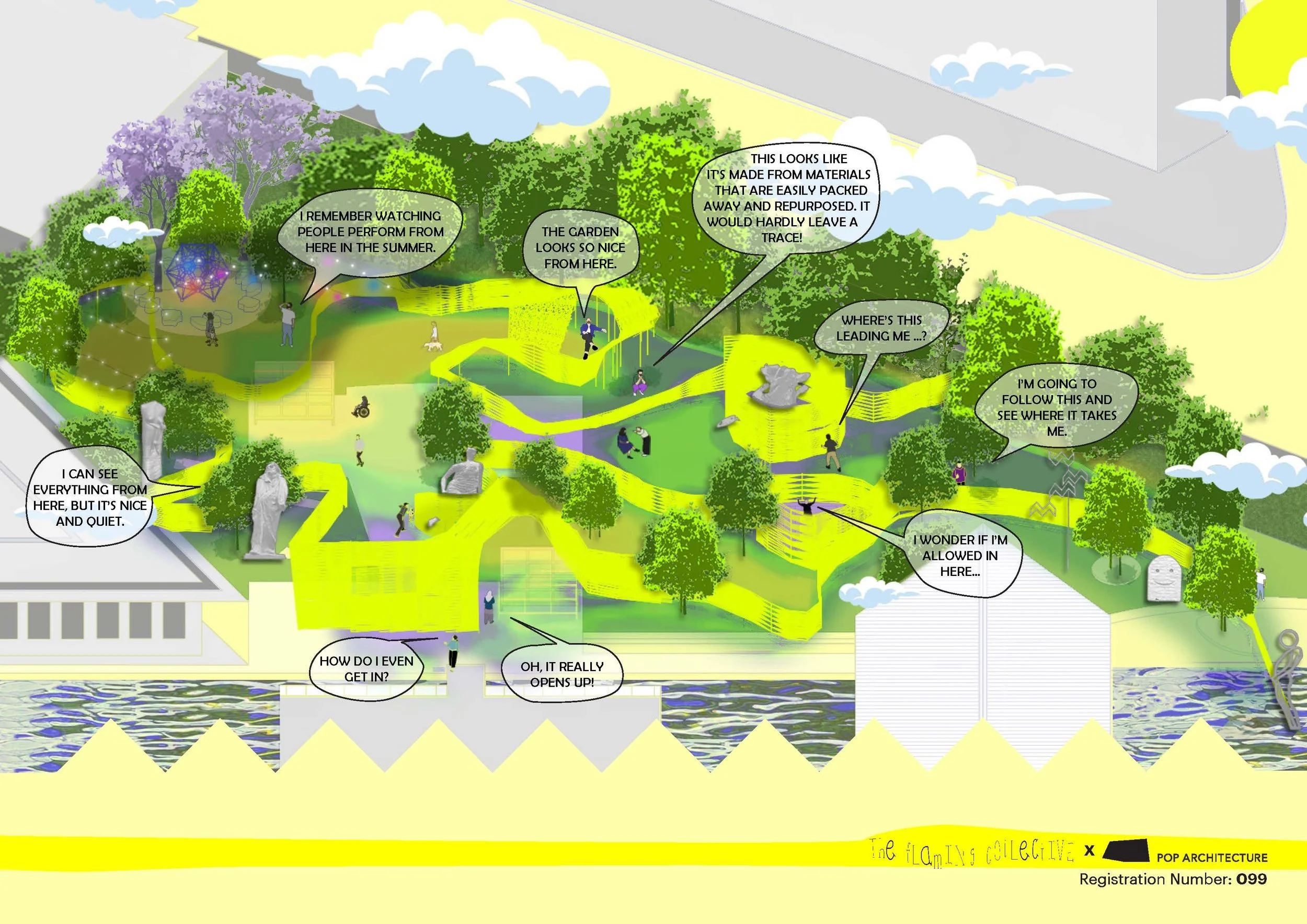

Article (written by Isla Sutherland for Australian Design Review)

As one of the country’s few female-led practices, Pop Architecture in Melbourne isn’t fixed on gender, but on the absence of ego.

“We were both in quite different places when we decided to start; it wasn’t particularly conscious or planned,” says co-founder and director Katherine Sainsbery. “I’d left Wood Marsh earlier that year and had a young child. Justine had taken a six-month industry sabbatical after leaving Architectus, and we connected late in 2016.” Sainsbery’s father, David Sainsbery, retired chief executive officer at Architectus, suggested she meet up with Justine Brennan, as a potential partner in business.

“We call it an arranged marriage,” Sainsbery laughs. The pair soon found they shared an affinity for each other’s rigorous process, design sense and dry wit. In December this year, the practice celebrated its fifth anniversary, with Pop formalised over Christmas drinks in 2016.

The practice acquired its initial work through interior designers. “I had strong professional relationships with a couple of different people: Karyne Murphy, who we worked with on the Fallow house, and Beatrix Rowe who we worked with on South Yarra,” says Sainsbery.

“We were really fortunate that both of those women, essentially sight unseen, recommended us and got behind us. They were both keen to support an emerging female-led practice,” says Sainsbery. This reciprocity has come to inform their working style.

“Because we received a lot of our early projects through two interior designers, straightaway we learned how to collaborate,” says Brennan.

“We both really enjoyed that from our previous jobs – the collaboration with consultants, builders and clients. It’s often one of the most beneficial parts of the project, and hence why Kat was referred by builders and interior designers from other projects.”

The duo says that their understanding of their role in the greater construction process, paired with their respect for others’ expertise, has helped forge lasting working relationships in the sector.

“As architects, we tend to design from the outside in, whereas the interior design approach can be different – designing from the inside out. It’s really forced us to think about it from that perspective as well,” says Sainsbery. “It’s a real push/pull of what’s more important.”

She adds that in finding themselves in the residential sector in particular, the practice has had to at times reprioritise this hierarchy. “Clients don’t always have an opinion on architecture or don’t feel particularly educated in that area to comment on it, but interiors are different. You’re so saturated by them that clients have strong opinions on the subject.”

The pair found their style and process were informed by a curiosity for the intersection of art and architecture. “The word ‘pop’ is not incidental or frivolous: we both like and appreciate pop art and, as common as that may seem, it’s more specific than that,” Sainsbery explains.

“We like the art, but we’re more interested in the process behind it. How pop art was produced in many cases, was that the artist had a concept and a production line generated it. That production line gave rise to many innovations and efficiencies to create something interesting and creative, but that had a stringent, rigorous process behind it.”

Sainsbery refers to the works of 1960s artists Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein. She and Brennan are interested in the way their art removes the artist’s hand, producing works via production line, which draws many parallels with contemporary architectural practice. “That’s something common to the way we both work: we both like process, we like something to be rational, but that doesn’t mean it has to look like a boring mass-produced box,” Sainsbery says.

“It’s also about understanding your place in the production line of construction,” she adds.

“As an architect, your medium is communication – you’re writing instructions for how to build a building. The thing that you produce isn’t the actual finished product. ‘Pop’ is about the ability to understand that and lean on people with more expertise to make projects better.”

The pair decided the reason they wouldn’t call their practice ‘Sainsbery Brennan’ – “apart from being a total snooze of a name,” Sainsbery jokes – is because they wanted a name that would encourage ownership from other people, both across a project and over the life of the practice.

The women are self-effacing when asked if they considered themselves anomalies as two female directors in a male-dominated sector. Brennan and Sainsbery have pushed along their practice of five while both have taken a stint of maternity leave, continuing to deliver an exceptional body of work while raising young families. Brennan theorises that the pair was perhaps better prepared for the unconventional work conditions enforced on the sector during COVID because they were already used to working under ‘flexible’ constraints.

Reflecting on their female-led practice, Brennan says, “Sure, it is a differentiator, but what clients say to us is they’re looking for people who will listen to them and to what they want, without an ego in the way. It’s something that’s been so reoccurring to the point where we’re like, ‘Is that really what the common experience of working with an architect is?’”

“Because we’re a relatively new practice, we don’t have this body of work behind us for people to see and say: that’s Pop. So we’ve really had to design each building for the site and for the client. There is obviously consistency in the things that we like in terms of design, but they’re also unique to the client and the client’s brief,” she says.

“I think we are looking forward to a time when we can be approached more for our unique architectural sensibility. But, in the meantime, it’s nice to be approached because people have heard you’re good to work with,” says Sainsbery.

While their humility is one of their great attractors, it can also pose its own challenges. “Running your own practice is very different to working in another firm – even in design-focused firms like we’ve been in – there, you put on the hat of whoever it is you’re working for,” says Sainsbery.

“But when we had the blank piece of paper in front of us, we were forced to interrogate our own design approach and philosophy.

“We’ve done a lot of that, and it’s been good and challenging. We’re very critical of ourselves and our work.”

This evaluative rigour really shows. Sainsbery and Brennan have created a practice that is sensitive to the surrounding environment and attuned to a client’s needs. Motivated by great design outcomes, their process generates considered and original forms, with an intimate understanding of space and materiality.

Link to full article on Australian Design Review